John Beaton

1875 - 1945

John Beaton, undated

Photo from the files of the Alaska Miners Association

John Beaton was born on August 9th, 1875, at Rear Little Judique (later St. Ninian), Nova Scotia, to Donald and Flora (nee MacLean) Beaton. John was the second oldest son in a family of six children. The Beatons, staunch Scot Roman Catholics, came from the Isle of Skye to Pictou, Nova Scotia, on the vessel Dove in 1801. Among the passengers was John's grandfather, Angus Beaton. Angus soon married Christine MacDonald. The Beatons had two children, Ann and John Beaton's father, Donald.

Angus Beaton was a farmer. Most of the men who arrived on the Dove were farmers, laborers, or tenants, but many bore ancient Scot names such as MacLean, MacDonald, and McLeod. The Beaton's clan name, MacBeth, is as old as any. Beatons trace their roots to Macbeth, King of Scotland from 1040 to 1057, A.D. After the death of Macbeth at the hands of Malcolm, it was perhaps expedient to drop the patronymic. Macbeths became Beatons or Bethunes. To escape the wrath of Malcolm and his descendants, many Beatons immigrated to Ireland, but gradually filtered back to Scotland. In the great period of migration from the British Isles that began near the start of the nineteenth century, many Scots migrated to Canada and the United States. The Isle of Skye, home of many soon-to-emigrate Beatons, was also the home of many of the strongest supporters of Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Catholic Stewart claimant to the thrones of England and Scotland in the eighteenth century. Many of those who left the Isle of Skye for Nova Scotia were members of the Catholic families who backed the last of the Stewarts during a time of Protestant ascendancy in Scotland.

John Beaton was a quiet man, but he must have retained something of the adventurous spirit of the Scot Highlanders. He left Nova Scotia in 1899 for British Columbia and shortly thereafter moved to the Klondike. Finding most of the opportunities in the Klondike gone, John arrived in Alaska in 1900, shortly after the Great Stampede to Nome in 1898-99.

John's travels in Alaska between 1900 and 1908 are uncertain, but John possibly mined in the hard rock mines of the Juneau area. In 1908 John and two partners began a prospecting enterprise in southwest Alaska, first prospecting in the Innoko district west of McGrath. The district was then in its early stages, following a discovery at Ganes Creek in1906. John's two partners were W. A. "Bill" Dikeman, a man of German descent from Nebraska, and Merton "Mike" Marston. When the men began to prospect the Iditarod country, they were also accompanied by John's younger brother Murdock. Only two of the men, Beaton and Dikeman, assisted by young Beaton, prospected. Marston stayed in town and worked any job available to purchase food and supplies for the prospecting venture. Marston's supplies must have been rudimentary; later John remarked that he had eaten "two tons of beans" in his prospecting years.

Beaton and Dikeman had little success in the Innoko district. In the fall of 1908, they decided to leave the Innoko district and prospect the Iditarod, a twisting tributary of the Innoko, in a region then virtually unknown. The men drove a steam launch down the Innoko and up the Iditarod as far as they could, beached the boat, and built a little cabin about eight or nine miles below the site of Iditarod. They then proceeded south into unknown mountains and began to prospect. On Christmas Day, 1908, Beaton, Dikeman, and young Murdock Beaton hit high-grade pay at a depth of twelve feet near the head of Otter Creek. The site was later named Discovery. Although most accounts indicate that the discovery shaft was the first in Otter Creek, Beaton later remembered that it was the 27th shaft that the two men had sunk on their prospecting venture that year. After their discovery and further prospecting, the men staked about a mile of Otter Creek for "themselves and a few friends," as stated by A. G. Maddren of the U.S. Geological Survey. One of those friends was Mike Marston, the third partner of the venture. According to the late Tony Gularte, who was in Flat in the early years, Beaton and Dikeman themselves staked alternate claims down Otter Creek.

Soon after the discovery, John Beaton returned to Nova Scotia to marry Florence MacLennan, the daughter of Neil and Mary (nee Chisholm) MacLennan in Inverness County, near his old home. John and Florence rushed back to the discovery site in Alaska and Florence was the first white woman in the new camp.

Because of the remoteness of the area, word leaked out slowly but by the summer of 1909, prospectors began to filter in and staked the remaining ground on Otter and its main tributaries. The pay on Otter Creek proved to be exceptionally wide, the widest paystreak ever mined in Alaska. When the Iditarod opened to navigation in the spring of 1910, there were at least two thousand people ready to stampede to the new district. Possibly as many as 10,000 men and women stampeded to Flat; almost certainly at least 4,000 came. Beaton's and Dikeman's discovery became the third largest placer district in Alaska, only exceeded by Fairbanks and Nome.

Among the first stampeders were Croatian immigrants Peter Miscovich and John Bagoy and his wife. John Bagoy's sister, Stana, soon joined the group and shortly thereafter married Peter Miscovich. Stana became fast friends with Florence Beaton. The camp was a lively one. Married couples like the Bagoys, Miscovichs, and Beatons had their own entertainment. But the more numerous bachelors were not left out completely. Each year the girls of the line held a Grand Pretzel Ball to honor their choice of Miss Otter Creek, and all were invited. Mostly just the bachelors attended.

Mike Marston joined Beaton in the new camp and the two men possibly mined together for the first years of the camp. Murdock Beaton left in 1909; his main purpose, to make a grubstake in order to marry his sweetheart, had been satisfied. Bill Dikeman apparently sold his claims to the Guggenheim-owned Yukon Gold Company soon after they entered the camp. But Beaton proved a canny Scot when he optioned his claims on Otter Creek to the Guggenheims, who were mining down Flat Creek from the rich Marietta claim. The Googs spent two years drilling out Otter Creek, but did not exercise Beaton's option price of $250,000. Beaton, however, with the drill data leased out his claims to individual operators running Bagley scrapers. Dikeman may have made a short-lived windfall when he sold his claims to the Guggenheims. Beaton did better in the long haul with royalties paid by several operators, while retaining the claims for later dredge operations.

Subsequently Beaton entered into a very successful mining partnership with brothers Gilbert and Bill Bates of Seattle, and with Harry Donnelly of the Miners and Merchants Bank. In 1916-17, the partners built a dredge on Black Creek where it competed against a Riley owned dredge. Beaton and his partners did well in Black Creek where some ground ran an ounce per pan. One reason for their success was their choice of foreman, "Big Lars" Ostnes. Ostnes not only was exceptionally strong, but was a good miner with several years experience in the district. Lars had just returned from Seattle with his bride Elise on the Princess Sophia. The couple had purchased round-trip tickets to expedite their return trip outside after the mining season.

In the early fall of 1918, Florence had an opportunity to leave Flat and travel to Seattle in part to let her two young children, Lauretta, age six, and John Neil, age four, visit relatives and have their first glimpse of Outside civilization. Originally Lars and Elise Ostnes had planned to return to Seattle on the Sophia, but Elise was six-months pregnant and they decided to remain in Flat. Elise sold her tickets to Florence.

The Princess Sophia, with three Beatons on board and much of the season's gold, left Skagway, Alaska, on October 23, 1918, but soon hit a reef. Early arrived ships, which might have been able to save a few passengers, were turned aside by the captain of the Sophia to await the arrival of another Canadian Pacific vessel. By that time, one-hundred mile-an-hour winds had smashed the Sophia and she went to the bottom with the loss of all on board, three-hundred and fifty-three souls. The event had an extra measure of tragedy for John. Beaton's mining partner Gilbert Bates reached Juneau first and identified a child as Lauretta Beaton. When John arrived at the make-shift morgue, he found that it was another child. The body of Lauretta was never recovered.

During his teen years, Beatson speculated on one endeavor far from the mining world. Possibly with Seattle partners Bill and Gilbert Bates, John built the old Strand Theater in Seattle. His theatrical venture was not particularly successful, but the mines at Flat continued to produce. In the highly competitive camp at Flat, John Beaton retained the respect of other operators and remained above most of the rivalry. He often aided other miners to become established. One of those men was Peter Miscovich. Beaton sold Peter a block of about 120 acres on a pay-as-mined deal. The land was adjacent to other lands acquired by Miscovich. The acquisitions enabled Peter Miscovich to begin a very successful mining operation and establish a family mining heritage.

Perhaps as an aid to mental recovery after Florence' death and to expand his horizons, Beaton bought a large cattle ranch in British Columbia, which he owned until 1927. On one trip outside in the early 1920s, John Beaton met a young widow, Mary "Mae" (nee MacDonald) Grant who had a daughter named Jean. John and Mae met at a dance in Boston, but soon compared notes and found that Mae was also a native of Nova Scotia and had grown up not far from John. John and Mae married on February 12, 1924 at St. James Cathedral in Seattle. On February 16, 1925, Mae had a son who the Beaton's named Neil Daniel. In 1927, John sold the ranch and returned to mining full time in Alaska. After the Guggenheims left Flat, Beaton's North American Dredging Company; a.k.a., the 'Beaton and Donelley Dredge', and the Riley Investment Company dredge shared an important part of Flat's production essentially until the early years of Alaska Statehood. In about 1937, Beaton, encouraged by his dredge manager Alex Matheson, began to look for new ground. Otter Creek had been mined intensively for nearly thirty years and according to Mathieson, was approaching its end. Beaton sold his outfit to Matheson. It appears that Mathieson and other men may have known that rich ground remained, and should have so advised Beaton, but kept their knowledge to themselves. Matheson rebuilt the 'Beaton and Donelley' dredge, immediately turned the boat back onto Guggenheim-mined ground, and extracted another fortune from gold left behind by the Googs.

Regardless, Beaton found other ground that he liked. It was close to where he and Dikeman had begun to prospect in 1908. Beaton went back to Ganes Creek in the Innoko district with his friend A. A. Shonbeck. Shonbeck and Beatson dredged there until World War II, and the creek is still not exhausted.

In 1936, John and Mae established a residence in Anchorage. One of the first things they did was to plant an apple tree, a tree that still flourishes in downtown Anchorage. Like many of his Anchorage contemporaries, John joined the Elks Club where he was sponsored by banker George Mumford and by Shonbeck whom John had known since 1910 in Flat. Beaton shared an interest in agriculture with Shonbeck and perhaps participated with Shonbeck in some of "double A's" many ventures in Anchorage and the Matanuska valley. Although John may have lost out in his transaction with Alex Matheson, the depression years seem to have had little negative effect on Beaton's life style. Both Jean and Neil attended private schools in Seattle. John and his new family enjoyed traveling throughout Alaska and "Outside." On those trips John and Mae were well dressed and looked the part of successful mine owners, which they were. But at the mines in Flat and at Ganes Creek, John, with overalls and a corncob pipe in his mouth, often looked more like one of the laborers than the owner.

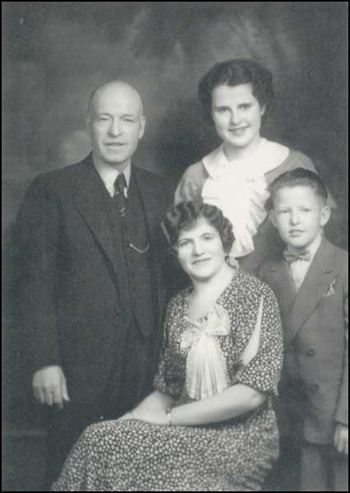

John and Mae Beaton, John's son Neil, and stepdaughter Jean Grant, circa 1936

Photo Credit: Ramstad Family Collection

Inside Alaska, John Beaton's extended family began to expand. His stepdaughter Jean married accountant-miner-contractor Joe Ramstad and raised one family. After a divorce, Jean married Francis Szymanski and raised another.

In late June 1945, Beaton and fellow pioneer Shonbeck were at Ganes Creek in the Innoko district to visit their placer mine - probably to consider reopening the mine at the end of World War II. Alaska mining man Hugh Matheson saw the men off in their truck. Except for trapper Cashmere Naudts, who was riding in the rear of the truck with his dog and was thrown into the river, Hugh probably was the last to see them alive. Shonbeck was driving and had a fatal heart attack as the men drove off a bridge abutment into Ganes Creek. The lock on the truck door jammed and it was hours before miners could retrieve the flooded truck and its fatal cargo.

Neil Beaton hurried home for the funeral from an Air Force training camp to join his mother and step-sister, then Mrs. Francis Szymanski. John Beaton's funeral was held in Anchorage on June 27, 1945 at the Catholic Church, with Father Dermot O'Flanagan presiding. Pall-bearers were Alaska old timers. John was buried in the Anchorage Memorial Park Cemetery.

Family members have continued Beaton's heritage in Alaska. After flying as an Air Force Navigator, Neil returned to Alaska and began his own mining and construction career, at times mining with the Ramstads at Golden Creek north of the Yukon. Neil's skill with massive construction cranes is still remembered by old-time Alaskans and his skill as an operator has rarely been equaled. Neil's children left mining, but Neil's daughter, also Lauretta, and her brother John retain family records and Lauretta pursues family history in prose and poetry. The second generation Ramstads and Szymanskis, although "step children" Beatons through their mother Jean, all consider John Beaton as "grandfather," and honor his accomplishments. The Szymanskis and Ramstads recently spearheaded efforts to re-monument the internment site for John, now joined again in death by his wife Mae and stepdaughter Jean.

In an obituary newspaper article published in Nova Scotia shortly after John's death, an unknown relative noted: "John Beaton was one of the fine type of Scottish Highlander who pioneered in distant lands and made good in many fields of endeavor. His heart was ever true to his native Nova Scotia and above all he loved to visit his old home and the scenes of his youth.... He was a loyal friend, a devout Catholic, kindly and cheerful despite more than the usual share of hardship and tragedy." In 1932, after a visit to Seattle, the Seattle Times characterized John Beaton as "small, quiet, calm" seemingly not at all the man whose life had been a series of "wild romantic adventures," who won and lost numerous fortunes, and who cheated death by minutes-all except the last time. That, nevertheless, was the life of John Beaton.

By: Charles C. Hawley; originally published in the December 2001 issue of 'The Alaska Miner'

SOURCES

The date of the marriage of John Beaton and Florence MacLennan is assumed to have been in early 1909; it might have been earlier but probably not much later.

Bundtzen, T.K., Miller, M.L., Laird, G.M., and Bull, K.F., 1992, Geology and Mineral Resources of Iditraod Mining District, Iditarod B-4 and Eastern B-5 Quadrangles, Alaska: Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys Professional Report 97, 46 pages, colored map @ 1:63,360 scale.

Coates, Ken, and Morrison, Bill, The Sinking of the Princess Sophia: Taking the North

Down with Her. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press; Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford

University Press, 1991.

Maddren, A. G., 1910, Gold Placer Mine Developments in the Innoko-Iditarod Region.

U.S. Geol. Survey Bulletin 480.

Staff, 1932, "Iditarod Discoverer in Seattle," Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, reprinted from the Seattle Times of January 17, 1932.

Staff, 1992, "The Sinking of the Princess Sophia," The Oran, Nova Scotia, Passenger list of the Dove, 1801. www.rootsweb.com/pictou/dovel.htm