Ellen (Nellie) Cashman

(1845-1925)

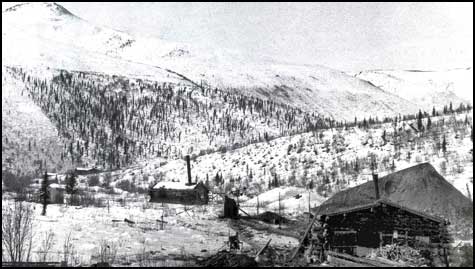

Nellie Cashman, undated

Photo: Alaska's Digital Archive

Nellie Cashman was a quintessential gold mining stampeder. She arrived with the vanguard at a new discovery and left, searching for her next opportunity, before the camp played out. Her searches for the next opportunity took her throughout the western United States, south into Mexico, and later into British Columbia and the Yukon Territory, Canada. Cashman's last gold rushes were the Fairbanks and Koyukuk-Wiseman districts of Interior and Northern Alaska. Nellie paid her way by establishing businesses, buying and selling mines, and mining. Excess dollars earned from these ventures, supplemented by funds she raised from her fellow miners, were used to establish schools, churches, and hospitals from the Mexican border to Alaska. At age sixty in 1905, Nellie settled down on Nolan Creek in the remote Koyukuk district in Alaska inhabited by miners who were as tough and self-reliant as she was. She died in 1925 at the hospital in Victoria, B. C. she had helped establish fifty one years before. It was a great adventure for a 'wee colleen' who left Ireland seventy-five years earlier with a widowed mother and sister to establish a new life in America.

Nellie was born in the farming village of Midleton a few miles from Queenstown (now Cobh) in County Cork, south Ireland, in 1845. Her parents were Patrick and Fanny (nee Cronin) O'Kissane, a family name later anglicized to Cashman. Nellie, christened Ellen, was baptized on October 15, 1845, probably not long after her birth. A sister, Frances or young Fanny, was born a year or two later. The Cashman family was Catholic and poor, categories synonymous with the years of the Irish Potato Famine. Family fortunes declined further when Patrick either died or left his family around 1850. It was then mother Fanny decided to immigrate with her daughters to America. They first settled in Boston where there were tens of thousands of Irish.

Fanny and her daughters left Boston in about 1865 for San Francisco. Some accounts state that the Cashmans first moved to Washington, D. C. At either Boston or Washington, Nellie, at about twenty years old, obtained a job as an elevator operator, an occupation reserved for men. As an elevator operator she met many interesting people and heard a lot of gossip. In a story that is almost certainly apocryphal, Nellie met General U.S. Grant on the elevator; he urged the young lift operator to go west where there was more opportunity. Regardless, in about 1865, Fanny and her daughters sailed south along the Atlantic coast and crossed the Isthmus of Panama probably on mules, then sailed northward to San Francisco. Like Boston, San Francisco had a large Irish population, and the Irish tended to look after their own.

Nellie's sister and youthful confidante Fanny met and fell in love with another Irish immigrant, Tom Cunningham. Tom was a successful shoe and boot maker, and sturdy boots were the need of every real or would be miner. Over the years Nellie had many businesses in the western mining camps and they often included sales of Cunningham boots. Cunningham died young, and Fanny, with five small children, pulled up stakes in San Francisco to follow her sister through western mining camps.

Nellie may have visited and worked briefly in other mining camps, but she first began to earn fame as a mining boomer in the restless silver camp of Pioche, Lincoln County, Nevada. Nellie and her mother opened a miners' boarding house on Panaca Flats, a milling center a few miles from Pioche, then one of the roughest mining camps in the west, perhaps only matched by Bodie, California. The Cashmans soon earned a reputation as good cooks, who were honest, and moral in a settlement that otherwise boasted seventy-two saloons and thirty-two brothels. The women probably arrived in Lincoln County in 1872 and left late in 1873 when there were signs that silver production had peaked and was heading down hill. Occasionally, as at Bisbee, Arizona, Nellie guessed wrong on the timing of a mining boom, but she had an uncanny ability to arrive with the first of stampeders and leave when a camp began to decline.

Cashman's first trip into the North Country was in 1874. Nellie joined a few friendly Nevada miners who rushed to the remote Cassiar district in British Columbia. Reportedly, they choose B.C. over South Africa on the flip of a coin. The Cassiar district had been discovered by Alexandre "Buck" Choquette about twelve years before, but there had been new discoveries near Dease Lake north of Telegraph Creek, and the camp was having a second rush. At Dease Lake, Nellie opened a combination saloon and boarding house, dealt in mining claims, and grubstaked miners, a pattern held by Nellie in later camps.

Nellie did well enough at Dease Lake to take a trip outside after the mining season. In the hard winter of 1874-75, Nellie heard that miners who had elected to winter over in the district were starving and suffering from scurvy. Nellie and five or six miners assembled emergency supplies and food, including limes to treat scurvy, and snowshoed hundreds of miles to rescue the miners. The errand of mercy was probably the first of many often well-publicized goodwill efforts that led Nellie to be called the Angel of the Mining Camps. Nellie contributed to or built churches, hospitals, and schools throughout the west. Although her most favored charities were Catholic, particularly the Sisters of St. Anne, Nellie contributed to the Salvation Army and other religious or civic groups. In Fairbanks, Alaska during 1904-5, Nellie supported the Episcopalian St. Mathew's hospital after it was already in existence and in need of funds.

The trip to the Cassiar was Nellie's first view of Alaska. Leaving Victoria, B. C., Nellie entered the new U.S. Territory via the inside passage and landed at Fort Wrangell, Alaska, before ascending the Stikine into British Columbia. The North must have caught her fancy, but it was about twenty-five years before she returned, first to the Klondike, then permanently to Alaska. Nellie ran her businesses and mined in the Cassiar during 1875 and 1876, but left in late 1876 to return to San Francisco where she took care of her aged mother.

By the time Nellie's returned to the southern territories, her reputation as a miner, businesswoman, and philanthropist was well established, and she had the means to form numerous businesses.

From 1877 until 1898, Nellie was at home in Tucson, or Tombstone, or Bisbee, or for shorter intervals in several other mining camps. She also led one ill-advised prospecting venture into Baja California. Nellie arrived in Tucson in the fall of 1878, in advance of the Southern Pacific Railroad, and immediately opened a restaurant, Delmonicos. The restaurant's billboards advertised Delmonicos as having the "Best Meals in the City." She advertised in the Arizona Weekly Star, newly founded and operated by Major John P. Clum who was impressed by Nellie. Years later Clum wrote:

"Her frank manner, her self-reliant spirit, and her emphatic and fascinating Celtic brogue impressed me very much, and indicated that she was a woman of strong character and marked individuality."

Only a few months after her arrival in Tucson, Nellie moved to Tombstone, one of the richest of the western silver camps then booming. In 1880-81, the population was about 5,000 with thousands more in the outlying camps. Nellie was joined in the rush by the Earp clan, by gunfighter-miner Don Neagle, and by John Clum, who quickly founded the Tombstone Epitaph, all on the law and order side and quite a few others of opposite stripe. In Tombstone, Nellie ran restaurants and retail businesses, some selling miners' boots manufactured by her brother-in-law.

Tom Cunningham died at age thirty-nine on February 20, 1881, leaving a young widow and five children. Nellie immediately moved the family to Tucson where Fanny could help Nellie with Delmonicos and other Cashman businesses. Unfortunately Fanny lacked the iron constitution of her older sister. She helped out as best she could, but gradually weakened by of tuberculosis, Fanny died on July 3rd 1884, and thereafter Nellie assumed all the responsibility for her nieces and nephews.

Some of Nellie's business practices can be discerned from her operations in the Harqua Hala Mountains about 80 miles west of Phoenix, Arizona. In November 1888, prospectors Mike Sullivan, Bob Stein, and Henry Watton (sp) hit rich veins of gold-in-quartz in the Harqua Halas. By early December, Nellie was provisioned and on her way to the new camp. She talked about opening a boarding house, but didn't. She did obtain some valuable claims however, and promoted the new district with articles published by Arizona newspapers. She understood the geology of the new district and wrote intelligently about it, predicting success for the district. In the long run, her predictions were accurate, but the hard rock ore proved difficult to develop and Nellie and original prospectors probably sold their claims within a few months of discovery. Nellie prospered from the sale of supplies and equipment and the sale of early-acquired mining claims whose values were promoted in her public statements and articles.

One unique aspect of the Harqua Hala enterprise is that Nellie may have fallen in love. The February 23 1889 issue of the Phoenix Daily Harold reported that Nellie and Mike Sullivan had left Mike's Bonanza mine to get married. Perhaps they fell out of love on the way to the preacher as nothing further was ever heard of the impending marriage.

After the Harqua Hala rush subsided, Nellie seems to have entered a restless stage, traveling throughout the west in search of gold or silver or related opportunities. Possibly Nellie traveled further: in November 1889, the Arizona Daily Star reported Nellie was back in Arizona visiting a friend and she had just returned from a trip to Africa. The trip has not otherwise been confirmed, but it is possible as there are substantial gaps in the record of Nellie's travels from 1889 to 1895. She flitted between Prescott, Jerome, and Yuma in Arizona and Kingston in New Mexico. In company with her nieces and nephews, then teenagers, Nellie prospected in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. In 1895, she made a quick trip to Juneau, Alaska, mainly to meet with old friends from the Cassiar district. But she usually returned to Tombstone or Tucson where she awaited news of the next big strike.

News of such a strike reached Nellie in about July 1897 when the vessel Portland landed in Seattle with gold nuggets and bags of gold dust from the Klondike discovery in northwest Canada. By November of 1897, Nellie was making plans to enter the stampede as Arizona newspapers reported her plans to organize an expedition to the Klondike. She staged her expedition from Victoria, British Columbia, putting together a Klondike outfit twenty-four years after her Cariboo district adventures. Nellie left Seattle for Wrangell, Alaska on March 13, 1898. Originally she had planned to go to the Klondike via the Cassiar district, but reportedly conditions along the trail were bad, and Nellie elected to take the Chilkoot route out of Skagway.

Nellie, then about fifty-four years old, arrived by herself in Skagway on the 20th of March. She had some help along the way, but not much. Nellie arrived in Dawson, Y.T. in mid-April 1898. Unlike many new to Dawson, she knew her way around a boom town and quickly established another 'Delomonicos' restaurant in Dawson while on the lookout for new mining claims. In most of Nellie's earlier jaunts, she had been the only woman. But in Dawson there were hundreds of women, and a few of them, like Ethel Berry and Belinda Mulrooney, were as tough and driven as she was. Nellie showed a litigious streak when she took a couple of these women to court and lost. Ultimately, though she acquired a good claim on Bonanza, No. 19 below Discovery, and mined it successfully. Later the claim sold for $100,000. As an Irish woman of her time, Nellie was not overly fond of the English and the English manner of administering the Klondike gold camp. When others proudly displayed the Union Jack, Nellie quietly showed the Stars and Stripes, and waited for an excuse to cross the border into United States territory.

Gold at Fairbanks, Alaska, was struck by Felix Pedro, an uneducated, but self-taught Italian immigrant, in 1902. In early 1903, Klondikers rushed to the district where they found deep frozen ground and many returned to the Yukon. The ground, however, was rich and the field was large. By 1904 serious mining was underway, and Nellie left Dawson. On her arrival at Fairbanks, she immediately opened a grocery store and began looking for ground, and undertook fund raising for the new Episcopalian St. Matthews Hospital. She set out to raise money for the new hospital by staking herself in some of the many poker games being played in by then the well-to-do mining camp.

It was time for Nellie to move on to one more mining camp. In 1907, Nellie Cashman, then sixty years old, packed her sled and embarked to the Koyukuk in the southern foothills of what is now known as the Brooks Mountain Range. The heart of the Koyukuk district is about 600 miles upriver from the mouth of the Koyukuk River, a south-flowing tributary of the mighty Yukon River. It is still remote, although now dissected by the Dalton Highway. During Cashman's time, the district was reached by shallow draft steamboats for about 450 miles to Allakaket, smaller boats to Bettles Trading Post, and up the Middle Fork of the Koyukuk for about eighty more miles to Wiseman and Nolan Creek. The district was explored by a Naval expedition in the early 1890s and prospected with some success by Alaska Mining Hall of Fame inductee John Minook, "Three-Fingered Miller", and other famed prospectors in the mid 1890s, about the time of another discovery at Rampart by Minook.

The best pay in the new district was underground on Nolan Creek, where the placer gold was buried by more than 100 feet of frozen, boulder-rich, glacial overburden. It was rich, but because of its remoteness, it had to be rich to return even a small profit. It was, then and now, a miner's district, and Nellie by this time in her life was an experienced miner. The miners in the district were by and large old and conservative. They seemed to thrive on whiskey, which appeared not to interfere with their mining. Men as diverse as Hudson Stuck, Robert Marshall, and in our time Ernie Wolff, thought that they were unique in Alaska. As summarized by Cashman's biographer Chaput:

"Every person on the Koyukuk could do practically everything. One had to be a blacksmith, a mechanic, steam engineer, logger, geologist, carpenter, baker, cook, dog musher and laundryman. A shirker was out of it, not respected, not tolerated."These were the kind of men that Cashman had lived with for forty years and she fit. If she lacked one or two skills, she hired a couple of men to help her.

Episcopal Deacon Hudson Stuck wrote about the Koykuk miners as: ". . . some of the best men that Alaska contains are to be found in the Koyukuk and I will not say that some of the worst are not there also." His counterpart, Bishop Rowe wrote that the men were conservative old timers,

"The type which has pioneered the way into this country for their fellow men, and who have the true spirit of the North. I do not believe that you will find a finer lot of men in any community than those Koyukuk miners."

Nellie was in the Koyukuk District when rich deep pay was found in Nolan Creek in 1908. Recognizing the need for thawing, Cashman went to Fairbanks and ordered steam boilers and piping for herself and other deep miners. The boilers enabled productive mining which lasted until about 1920, when further modernization or increase scale of mining was needed.

Nellie Cashman's cabin on the left limit of Nolan Creek, circa 1909

Photo Credit: Harry Leonard collection

Nellie did well in those years and made a habit of leaving the district in the winter to visit family and friends, including her favorite nephew Mike Cunningham, who was a successful banker in Bisbee, Arizona. Nellie was still capable of mushing her dogs hundreds of miles on her trips in and out of the district. The Associated Press documented one dog mushing trip that she made from Nolan to Anchorage in 1922. When she completed a 17-day 350 mile trip from Nolan Creek to Nenana in December, 1923, newspapers all over Alaska again carried the travels of the seventy-eight year old intrepid miner by the name of Nellie Cashman. In the early 1920s, Nellie and others tried rather unsuccessfully to promote and raise money for larger operations, at the same time maintaining a small production. The times after WW I were not auspicious for gold mining capitalization. Younger men, earlier abundant labor, had been lost to the war, and the fixed price of gold at $20.67 per ounce bumped against wartime inflated costs. In 1921, Nellie visited California, where she declared that she would like to be appointed U.S. Deputy Marshall for the Koyukuk mining district, but this aspiration never bore fruit.

In the summer of 1924, Nellie realized that her health was slipping rapidly. She stopped briefly at the St. Ann's Mission in Nulato, then went up river to Fairbanks, where she was admitted to St. Josephs Hospital, then sent to Providence Hospital in Seattle. Recognizing that her time was almost up, Nellie went to St. Ann's Hospital in Victoria, which she had raised funds for in the Cassiar decades before. Nellie died on January 4, 1925 in the company of Alaska Sisters of the Order.

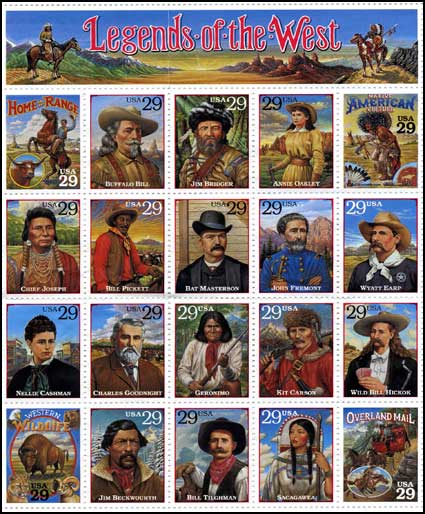

The remarkable pioneer described here is remembered in many ways. 'Nellie Cashman Day' is celebrated in Tombstone, Arizona on the eve of Women's Equality Day' to commemorate "heroic and liberated women of the 1880s". Tombstone's 'Nellie Cashman Restaurant' still stands next to a business originally established by her. Alaska was Nellie's last stampede and it was the only place where she settled down and mined. It seems appropriate that Nellie was honored by the Alaska Mining Hall of Fame in Fairbanks, Alaska in 2006, almost exactly a century after her residency in Fairbanks. Nellie Cashman was immortalized on a 29 cent stamp issued by the United States Postal Service in October 18, 1994.

United States Stamp plate issued 1994 honoring 'Legends of the West.' Nellie Cashman in lower left.

By Charles C. Hawley and Thomas K. Bundtzen, 2006

This biography was completed from dozens of articles and several books about the life of Nellie Cashman. One of the best is the thoroughly researched and documented account by western historian Don Chaput. Several other references are also listed below.

Photos And Facsimles Courtesy Of Alaska State Library

SOURCES

Don Chaput, 1995, I'm Might Apt to Make a Million or Two: Nellie Cashman, and the North American Mining Frontier. Tucson, Westernlore Press.

John P. Clum, 1931, Nellie Cashman, Arizona Historical Review, v. iii, 9-34.

Ronald Wayne Fischer, 2000, Nellie Cashman: Frontier Angel, Talei Publishers.

Melanie J. Mayer, 1989, Klondike Women: Ohio University Press, 267 pages.

Mike McCormack, 2003, An Irish Angel in America's West: St. Patrick's Press, 21 pages.

Claire Rudolf Murphy and Jane G. Haigh, 1997, Nellie Cashman, in, Gold Rush Women: Alaska Northwest Books, p. 112-116.