Charles (Chuck) Francis Herbert

(1910-2003)

Charles F. Herbert, circa 1970.

Photo courtesy the Jack Roderick Collection.

Slight of stature, quick with a smile, he was a giant of a man in Alaska's mining circles;" wrote an Anchorage Voice of the Times editorialist to describe Charles F. Herbert at his death in 2003. The writer also called him tough, smart, adventurous, lucky, and civic-minded, all adjectives necessary to describe Herbert during a nearly 80-year love affair with Alaska. He arrived in Alaska in 1926 as a sixteen year old high school graduate ready to take on any challenge. He stayed until poor health and a propensity for broken bones drove him to the Hawaiian Islands where friends and family could at least subtly supervise an always independent man.

Charles Francis Herbert was born on February 17, 1910 in Cincinnati, Ohio to Joseph and Maude, nee Johnson, Herbert. His parents were well educated and interested in the arts. Joseph studied at the Chicago Art Institute, but moved to Cincinnati to engage in business and raise a family. Chuck was the oldest of siblings, four brothers, William, twins Robert and Richard, Edward, a sister Caroline who was the youngest. His mother Maude was a serious musician, if one whose main role after her marriage was family. A native of Wisconsin, Maude attended the Chicago Conservatory of Music. She was sufficiently talented that she performed the Grieg A Minor Piano Concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Chuck's interest in mining came from his paternal grandfather, a man of Danish descent, who mined in the Rocky Mountain states. After graduation from high school in Cincinnati, Chuck left home and worked his way across the continent and sailed steerage to Alaska. He had an objective - to be a professional mining engineer. He worked to attain that objective, alternately studying mining at the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines in Fairbanks and working at whatever mining jobs that he could find. In the late 1920s, Chuck was a miner at the Kennecott mines near McCarthy, surviving the rough hazing especially meted out to young college lads. As Chuck gained some formal mining knowledge, he found employment as an assayer at the Lucky Shot mine in the Willow Creek country. At Lucky Shot, Herbert worked for Wesley Earl Dunkle, a leading economic geologist and mining engineer of his time. Both men had a quizzical sense of humor: Chuck remembered one afternoon when the two of them spent several hours liberating a large boulder above the mine, then watched, laughing hysterically as it cascaded down the mountain. Mining activities in the Hatcher Pass district provided Herbert with valuable experience related to the development of hardrock mineral resources. At the time, Dunkle's Lucky Shot mine was one of the richest and best managed gold mines in the United States.

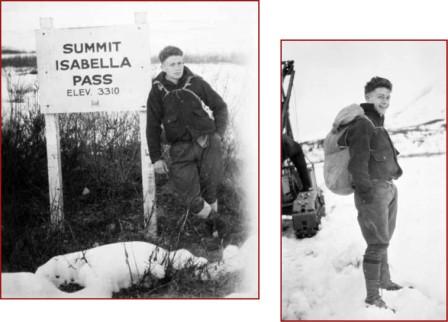

Chuck Herbert, circa 1929. Note, Isabella Pass is now known as Isabel Pass, and is on the Richardson Highway, less than two miles north of Summit Lake.

Photos and caption from Alaska's Digital Archives.

Chuck returned to the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines in Fairbanks in 1934, where he earned a B.S. degree in Mining Engineering. He was senior class president, graduating Magna Cum Laude. It was a rather auspicious time to be a mining engineer graduate. America was in the midst of the Great Depression, but gold mining was thriving under the impetus of raised gold price and deflation of most costs. Chuck found employment and joint ventures, first working in Alaska's Forty Mile mining district. Before Herbert gained a reputation as a leading independent dredge miner, he was thought of as one of Ernest Patty's 'boys'. These boys, more accurately described as men and including a young woman, Alaska Mining Hall of Fame inductee Genevieve Parker, had studied mine engineering under Dean Ernest Patty at the college. Chuck and a few others, including later well-known placer engineers Bruce Thomas and Bill O'Neill, worked for Patty as he established dredge operations at Coal and Woodchopper Creeks and extended his outreach into the Yukon. Herbert's undergraduate School of Mines thesis, "Gold Dredging in Alaska", is one of the best contemporary summaries of dredging. It benefited from the close association that students like Herbert had with the FE Company, then operating a dredge fleet at Fairbanks, and with successful independent gold dredgers, including Alaska Mining Hall of Fame inductee Thomas P. Aitken, who served as an advisor to the college.

During the mining years of the mid-30s, Chuck married Sarah Ann (Sally) Stephens and fathered two sons, Paul and Steven. Both boys grew up in Alaska and prospected with their father in the Fortymile, at Livengood, and in the Brooks Range

In the late 1930s, Chuck put his hard-gained practical and academic experience to work for the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), the depression-spawned Federal agency that subsidized new industry, including gold and platinum mining in Alaska. One significant project that involved Herbert was the RFC loan to the Goodnews Bay Mining Company. The loan, which was repaid within a year, enabled the firm to install a large Yuba floating dredge on the Salmon River of southwest Alaska. The Goodnews company became the largest producer of platinum metals in the United States for nearly 40 years.

Students of the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mining, 1929-1930. Arrow shows Chuck Herbert.

Photo from the Otto Geist Collection, Rasmusson Library, University of Alaska-Fairbanks.

With the coming of World War II, shortly after his election to the Territorial Legislature, Chuck joined the Navy. As a SeaBee, the US Navy engineers, Herbert managed construction projects throughout the Pacific theater. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant Commander, but returned to mining at wars end.

In 1946, after the war, Chuck joined Glen D. Franklin, Harold Schmidt, and Leonard Stampe to form Yukon Placer Mining Company, organized initially to pursue mining opportunities in Walker's Fork, Canyon Creek, and Jack Wade Creek in the Forty Mile country of east-central Alaska, near the Canadian border. The men successfully operated a gold dredge mine on the Sixtymile River and an open cut placer gold mine in Glacier Creek in an adjacent part of the Yukon Territory.

Another Herbert success story took place north of Fairbanks. The large but deep and complex placer gold deposit at Livengood had never been successfully mined on a large scale, and the mine closed down before World War II. The mine had RFC backing, and the RFC tried to get Fairbanks Exploration Company (FE Company) interested in mining the deposit. In 1953, the FE Company purchased the Livengood dredge, but instead of using it to mine the promising but challenging Livengood Bench system, the Company moved the dredge to the remote Hogatza district of northwestern Alaska. In 1954, after legal foreclosure, the RFC auctioned the Livengood property off. Chuck, with Glen Franklin and partners, acquired the placer deposit and mined it successfully with a dragline and elevated sluice for a number of years, despite the fixed price of gold at the time.

Although noted as a placer miner, Herbert retained an interest in prospecting for hard rock resources, especially in Alaska's Brooks Range. It was an interest that he shared with prospector Rhinehart (Rhiny) Berg. Rhiny had prospected in the Wrangell Mountains before World War II, but believed that he would make a major strike in the Brooks Range, which he had first seen as a wartime Alaska Scout. After the war, Rhiny engaged famous bush pilot Archie Ferguson of Kotzebue to land a prospecting outfit west of Kobuk on the southern flank of the Brooks. Chuck Herbert, aviators at Kotzebue and Kobuk, and Jack and Edith Bullock of Kotzebue Tug and Barge, Inc., grubstaked and advised Rhiny. Berg discovered a large copper deposit at present Bornite, Alaska and sold it to the Bear Creek Mining Company, a subsidiary of Kennecott Copper Corporation. Rhinehart Berg shared a multimillion-dollar pay off with Chuck, the Bullocks, and the natives who had assisted him in prospecting.

Prospecting in the Brooks Range almost cost Herbert his life. In 1957 while on a prospecting venture, Chuck, son Steve, and Eskimo prospector Tommy Douglas survived an airplane crash which killed the pilot. Their aircraft could not conquer the downwind flow in a narrow pass and plowed into the mountain. In the accident Chuck, already handicapped by loss of an eye to cancer in 1950, was badly bruised with a severe arm fracture. Tommy Douglas lost a leg as a result of the accident. Steve Herbert earned a Carnegie medal for his role in saving the lives of his father and Douglas.

Politically, Chuck was a Democrat, and was close to William (Bill) A. Egan, who in 1959 put together a team for Alaska's first gubernatorial race. Egan wanted old friend Chuck Herbert on the team. To avoid any conflict of interest, Herbert sold his interest in Yukon Placer Mining Company to remaining mining partners Franklin and Schmidt and joined the ultimately successful Egan team. Chuck's first assignment from Governor Egan was to set out procedures for and manage the public utilities of the new state. In effect he set up a utility management system, the forerunner of today's Regulatory Commission of Alaska. With the successful conclusion of that task, Governor Egan wanted Chuck in a more sensitive political position, that of Deputy Commissioner of the Department of Natural Resources (DNR). The governor thought that his Commissioner of DNR, Phil Holdsworth, and the powerful Director of the Division of Lands, Roscoe Bell, might be too easily influenced by oil lobbyists, who were then jockeying for a land base with petroleum potential for their clients. Egan wanted someone whose judgment he could trust as a counterbalance, and he chose Herbert. Chuck himself never doubted the integrity of Holdsworth and Bell, but he accepted the deputy position where he had direct access to the governor. Herbert quickly became involved in some of the earliest state land selections as promised in the Alaska Statehood Act. DNR geologist Tom Marshall and Commissioner Phil Holdsworth had identified a selection near the remote and then practically unknown Prudhoe Bay on the northern coast of Alaska which they thought was rich in oil - a belief downplayed by many professional petroleum geologists. The selection would be large and Governor Egan was not fully convinced by Marshall's and Holdsworth's arguments. Holdsworth sent Herbert to lobby the governor, a move which helped finalize the critically important Prudhoe Bay land selection. Gil Mull, one of Atlantic Richfield's pioneer geologists at the Prudhoe Bay discovery well, remembers that the savvy Deputy DNR Commissioner Herbert helped consummate the land selection by avoiding a conflict with the federal government over the issue of navigable rivers. By selecting lands adjacent to the coast, the State of Alaska avoided the specter of a long term dispute with the federal government, which could have derailed the Prudhoe Bay selection.

In late 1966 and early 1967, Chuck also served Governor-elect Walter J. Hickel, who retained Holdsworth, Bell, and Herbert for a few months until he could field his own Natural Resources team. The potentially valuable oil lands had been selected in the Egan administration, but the onshore and offshore lands at Prudhoe Bay had yet to be leased. Former Governor Egan, who lost to Hickel in 1966, had held off in offering the critical Prudhoe Bay leases, partly because he did not believe in rushing into deals with the oil companies and partly because Alaska's native groups threatened a law suit if the sale proceeded before a Native lands settlement was concluded.

Hickel moved aggressively with the leases, and DNR holdover Chuck Herbert helped organize the lease/sale. Hickel succeeded in resolving native fears and the lease-sale proceeded. An Atlantic Richfield drill hole started only weeks after the lease/sale in January 1967, shut in during the muddy summer months, was finally completed in the spring of 1968, when oil flowed at thousands of barrels per day. It was the Prudhoe discovery well.

Later in 1967, Governor Hickel brought in his own team headed by independent oilman Thomas E. Kelly and Chuck returned to his first love, the mining and mineral exploration business. In 1968 Herbert was retained by Newmont Mining Company to coordinate an exploration program for platinum metals. The crew prospected and evaluated most of the important known platinum metal occurrences in Alaska: Goodnews Bay, Kowkow, Mount Hurst, and Boob Creek in western Alaska and Salt Chuck on the Kasaan Peninsula in the Panhandle. Alaskan geologist Paul Glavinovich was on the crew and remembered one incident illustrative of Chuck's style, strong on leading by example. The crew had been pinned down by weather for three days and there was no let up in sight. In the afternoon of the third day, Chuck began pulling on his rain gear. Paul noted:

"he [Chuck] stated that although he could not reach the high ground he felt that he could still be productive if he could get into the lower creeks to check the float . . . available outcrops, and do some panning."Paul decided to join Chuck, even though he had not asked for volunteers. With those examples, the rest of the crew suited up and went to work.

In 1970, Chuck joined the second Egan administration as the Commissioner of the Department of Natural Resources. It was a critical job at a critical time, especially in regard to the State's land selection process. Prudhoe Bay, some valuable near-urban lands, and some coal lands were early targets of selection. But most of Alaska's 104 million acre entitlement was still in Federal hands. Land selection under the Statehood Act had been precluded since late 1966 by Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall's land freeze, pending resolution of native claims to public lands.

It appeared that Alaska's land selections might be back on track when Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in December, 1971. But the act also established new restrictions on selection and gave native corporations preferential rights to select 44 million acres of Alaska land. Moreover Section 17 (d) (2) of the ANCSA Act recommended that 83 million acres be studied for inclusion into Federal conservation units such as National Parks, Wildlife Refuges, and Monuments, which would preclude natural resource development. Extensive withdrawals of Federal land were made under Section 17 (d) (1), and froze Alaska's rights to select lands as mandated in the 1959 Alaska Statehood Act.

Pending identification of these lands, Alaska had a limited opportunity for selection in early 1972. The Commissioner moved rapidly. Herbert's staff, which included the respected oil geologist William C. Fackler, focused on the selection process, and Herbert appealed to the private sector, mainly to miners who knew rural Alaska better than anyone except native first residents. In January, the State filed for tens of millions of acres of land, infuriating Secretary of Interior Rogers C. B. Morton who reacted with threats of litigation. Against Herbert's belief and advice, Governor Egan settled out-of-court with Interior cutting the selections. Commissioner Herbert believed, probably rightly, that the extensive selections would serve as a buffer in the coming battle on conservation lands.

Alaska's long-time Governor's representative in Washington D.C., John Katz, remembers the important contribution that Herbert made during this crucial time in the new state's history. "I think Chuck felt the need to accelerate the State selection and conveyance process. Quite rightly, he believed that subsequent events would open large areas to State Selection. So in this context, Herbert's land selections had two purposes: 1) to vest legal rights where possible; and 2) to put down a marker for Congress and the Interior Department. Chuck's land selections did help the Alaska national interest lands debate throughout the 1970s by identifying particular State interest in land parcels. I also think that the transportation and access provisions to land selection titles in the 1980 ANILCA act were a direct product of Chuck's concerns.”

Chuck Herbert served on the joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission (FSLUPC), a unique body set up by Congress during the 1971 passage of ANCSA. The FSLUPC served as an important counter balance during Alaska's land battles with the federal government, until the passage of ANILCA in 1980.

One of Herbert's objectives during his tenure as DNR Commissioner was establishing a more credible State presence in the fields of geological mapping and geophysical investigations. In 1971, acting on the advice of veteran state geologists Gordon Herreid and Crawford (Jim) E. Fritts, many geologists in the private sector, and his own desires, Herbert reorganized DNR's Division of Mines and Geology into the Alaska Geological Survey, with William C. Fackler and Donald C. Hartman serving as the first two State Geologists. Interestingly, a final name change in 1973 to the Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys reflected, in part, Governor Egan's personal interest in airborne geophysical investigations as a tool to evaluate minerals on Alaska's lands. DGGS Professional staff member Mitchell Henning remembers Commissioner Herbert as:

"down-to-earth. . . showing a keen interest in the professional work of ordinary DNR geologists, stopping by the Geological Survey offices on a monthly basis"

Chuck and Egan had a major falling out over future ownership of what would become the Trans Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS). Egan and the majority of his Commissioners favored State ownership of the Pipeline. Herbert, with more experience in the private sector, argued against public ownership because he distrusted the State's efficiency and its ability to respond in a timely fashion to the problems that were sure to arise during construction. Chuck could never convince the Governor of the correctness of his views, but was perhaps vindicated when the TAPS, which was supposed to cost about $1 billion, cost nearly $10 billion by the time it was completed, a burden that could have broken the new state or buried it deeply in debt.

Both Herbert and Egan shared blame when Governor Egan lost to Republican Jay Hammond in 1974. One very contentious campaign issue was the buyback of the Kachemak Bay oil leases. Prior to the leases, a petition signed by hundreds of residents of the lower Kenai requested a hearing on their concerns regarding possible oil-drilling caused damage to the sensitive marine environment off Anchor Point. Herbert, with at least tacit support from Egan, denied the requested hearing. As reported by oilman Jack Roderick, Herbert wrote,

"No specific issue or problems were raised."The lease sale proceeded in December 1973. The decision to proceed without a hearing angered many otherwise strong supporters of Egan. Hammond's margin of victory was so small, that a decision to grant the hearing could well have changed the result of election.

Herbert and Egan disagreed on several issues, but remained close friends and regardless of differences, Herbert always believed that no one could approach Bill Egan's love of Alaska and its people.

Herbert served out Egan's second administration, and then at age sixty-six, returned to the Brooks Range. BP Minerals, the hard rock subsidiary of the major oil company, proposed to prospect Alaska and they wanted an experienced Alaska man to lead the effort. BP-Mineral's Canadian manager, Donald Mustard, hired Chuck to set up the program. The exploration team headquartered out of Bettles and worked east and west along the Range, although leaving the Kobuk-Bornite area mainly to Kennecott. Legislation that passed Congress in 1979 blocked access to much of the southern Brooks Range. BP-Minerals pulled out of Alaska a few years later, but not before Chuck had built up a good exploration team that made discoveries that were never drill tested. Steve Enns, Alistair Findlay, Andy Chater, Nate Brewer, and other members of the BP-Minerals team carried Chuck's name and reputation around the mining world-- South America, Mexico, Mongolia and Western and Eastern Canada.

During the BP-Minerals years, Chuck received a signal honor from his Alma Mater in Fairbanks. At the first ever School of Mines Alumni Banquet in 1978, Chuck Herbert was named the first Outstanding Alumnus of the School. It was a special honor, as he was competing against internationally known placer engineers such as Patrick O'Neill and educators including Ray Smith, President of Michigan Tech University. Chuck's citation noted:

"As deputy commissioner of Natural Resources, Chuck Herbert played a principal part in the state's selection of oil-rich Prudhoe Bay . . . as commissioner of Alaska's Dept. of Natural Resources from 1974 [he] approved the state right-of-way lease for the Trans-Alaska pipeline."

The BP-Minerals venture that began in 1975 took Herbert well into his 70s. Paul Glavinovich kept Chuck working for a few more years. Glavinovich, who had moved from Newmont to Noranda, engaged Chuck to advise on the feasibility of dredge mining the placer gold deposit at Mud Creek near Candle (Seward Peninsula). He also sought Chuck's advice on methods of recovery of the fine-gold on the beach sands near Yakataga along the Gulf of Alaska coast.

In 1982, Herbert presented the paper 'Alaskan Placer Mining' at an A.I.M.E. meeting held in San Francisco. In that paper, Chuck stressed the importance of searching for deeply buried gold and platinum placers as well as the promise of recovering ultra-fine gold from previously mined areas and marine strandline deposits. Indeed, the excellent presentation reflected a true expertise and depth in the placer mining field, where Herbert's long Alaskan career had begun.

Throughout the late 1970's and into the 1980's, Herbert continued to work on behalf of Alaska's mining industry. As friend and lawyer James Reeves relates:

"Chuck had a fairly serious heart attack (or stroke) right before my eyes in the reception area of my law firm when we were working on the Statehood Act6(i) lawsuit, which was challenging the way in which State lands were being managed for minerals. He was rushed to the hospital, but predictably, he was out of the hospital and back into the fray before practically anyone had noticed."Chuck would remain a quiet but always knowledgeable advisor and friend to the mining industry into the early 1990s.

For decades, Chuck Herbert's career had been stabilized by an exceptional second marriage. In 1953, Chuck married Roberta Roberts McInerney. Roberta was also an Alaska expert; she knew the Alaska Highway as well as anyone from the twenty or so trips up and down it canvassing lodges and recording mileages for The Alaska Milepost. Although the Herberts were quiet socially, they were gracious hosts. Their home reflected their interest in Alaska art and artifacts. Works by their favorite Alaska artists, Eustace Ziegler, Marvin Mangus, Rie Munoz, and Jenny Lind adorned the walls. Roberta died in 1989 after a year's battle with cancer. Chuck never recovered completely from the loss.

Chuck and Roberta Herbert at Livengood, Alaska, circa 1954.

Photo courtesy of Jamsie Herbert.

In the early 1990s, Chuck Herbert broke his hip at his home in Anchorage. At his son Steve's insistence, Chuck moved to Hawaii, but remained on his own. In his last year, Chuck's remaining vision began to fade and at last he felt immobile, but his intellect never faltered. Charles F. Herbert, Alaska's premier miner of his generation, died at Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, on September 3, 2003.

By Charles C. Hawley and Thomas K. Bundtzen, 2006.

SOURCES

Anchorage Voice of the Times, Chuck Herbert: An Alaska Mining Legend, Anchorage Daily News, September 14, 2003, p. H-3

Glen D. Franklin, in Charles F. (Chuck) Herbert Remembrances, Alaska Miner, v. 31, no.10,, p10

C.F. Herbert, 1934, Gold Dredging in Alaska: Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines B.S. Thesis, 98 pages.

C.F. Herbert, 1982, "Alaskan Placer Mining”: Presentation given at the American Institute of Mining Engineering (A.I.M.E.) annual meeting, San Francisco, California, 7 pages.

Paul Glavinovich, as above, in Remembrances p. 10-11

Leslie M. Noyes (collaborators Earl Beistline and Ernest Wolff), 2001, Rock Poker to Pay Dirt: The History of Alaska's School of Mines and its Successors University of Alaska Foundation: Fairbanks, esp. p. 425, 427,429, 441, 479,492-93, 508, 603

Jack Roderick, 1997, Crude Dreams: A Personal History of Oil & Politics in Alaska, Epicenter Press: Seattle/Fairbanks, p.109, 210-211 336-337

Clark C. Spence, 1996, The Northern Gold Fleet: Twentieth Century Gold Dredging in Alaska, University of Illinois Press: Urbana/Chicago,.p 140, 168

Carolyn von Stein (Chuck's sister), letters to author, 2003

Steve Herbert, various written and personal correspondence, 2003, 2006.

John Katz, written communication, October, 2006

James Reeves, written communication, October, 2006

M.W. Henning, personal communication, October, 2006

G.C. 'Gil' Mull, personal communication, 2006